Words by Kimberly Haddad

After committing more than 30 years to honing his craft, Timothy White has become one of the world’s most sought-after celebrity photographers. With an impressive portfolio that includes iconic figures like Al Pacino, Brad Pitt, and Ray Charles, White clearly has a gift that enables him to form genuine connections with anyone willing to pose for his camera. Through his keen sense of timing, White consistently freezes fleeting moments in the most powerful ways.

Crediting much of his success to his upbringing in New Jersey and the particular attitude that came with it, White fondly remembers the early days of his career beginnings as a bit of a wild card. He would pedal around the streets of New York City on his bicycle, carrying a portfolio under one arm and gripping the back of passing trucks to glide through the bustling avenues. After presenting Rolling Stone with a series of portraits from his travels in South America, White was promptly given the opportunity to photograph Yoko Ono in 1984. This moment was pivotal and marked the start of a much larger career trajectory than he had envisioned.

Today, White has taken portraits of numerous public figures, but amid the assumed pressure of his high-profile work, he approaches every shoot with the same humility and sincerity he had as little Timmy from New Jersey. To White, every snapshot is a deliberate act of artistry, from the initial interaction of the relationship on set to laying bare his truth in the final frame. Each photograph tells a story, a subtle or bold narrative depending on the subject, but always preserving a special point in time that will never be replicated.

How do you think the cultural and social environment of Englewood, New Jersey shaped your artistic vision and style in photography during your upbringing?

Oh my, that’s major. I think there is something that comes with being from New Jersey. It’s an attitude, but not a bad attitude. It’s in the shadow of New York City, but yet, they still hold their own. Everyone will have their own opinion, but there is something about New Jersey that breeds a certain kind of person. They have a very unique personality. I think it’s that, plus the way I was brought up. I was confident and independent, and I think that also really affected my career, my sense of self, and how I wanted to bring my own experiences into a photo shoot. I hosted an exhibition at the Newark Museum of Art in New Jersey and I called it “What Exit” because that’s such a common Jersey phrase. If you’re from New Jersey, people always ask what exit because the turnpike and the parkway run from the top of the state to the bottom of the state. It’s a determination of where you are. It was kind of funny. I’ve been inducted into the New Jersey Hall of Fame, which is something I’m very proud of. I have photographed so many people from New Jersey. Whether it’s Jack Nicholson, Bon Jovi, Bruce Springsteen, Danny DeVito, or Susan Sarandon—I mean, the list goes on and on—there’s just something about the state that brings out a certain personality.

When you first learned that you would be photographing Yoko Ono for Rolling Stone, what thoughts crossed your mind, especially considering that this assignment was the one that truly launched your career?

At the time, Rolling Stone was the bar for where I wanted to be. I wasn’t going to be a lawyer and I wasn’t going to be in business. I was looking for something different. I was into music and photography seemed like something I could do. I wasn’t extremely talented as an illustrator or anything like that, but photography made sense to me. Music and photography started to come together and after I left art school, I moved to New York. I was photographing bands and trying to build a portfolio. I had actually done some travel work in South America. I shot a lot of portraits of real people and that was the work that Rolling Stone responded to right away. They were the benchmark for me. They were where I wanted to be as a photographer, and the magazine was also changing as the culture was shifting. I went in to show them my work from South America and they hired me right away. It affected me because in my mind, this was something I knew would elevate my career and where I was going.

In photography, I believe there is a delicate balance between glorifying and humanizing celebrities through images. What ethical factors do you consider when capturing subjects in a raw portrayal that goes beyond their public persona?

I walk into every shoot, and it’s just me. I’m little Timmy from New Jersey. I’m still that guy. My father used to always tell me that whether it was the janitor or the head of a company, I treated them the same way. It’s just the way I was brought up. I engage with people in a certain way and try to elicit reactions from them. A photograph is not truth. It’s not a true representation of a person. It’s my truth. It’s the way I see them. I create through the lens, film, lighting, color, tone, whatever it may be. I manipulate all of those pieces and then, with my personality, I bring something out of them and get them to react to me. I’m in control of the pieces and I get them to give me a genuine one-on-one reaction.

During a past interview, you referenced a quote by Richard Avedon stating that photography is not the truth, but instead an illusion that reflects personal truths and opinions. How do your own experiences and biases shape the way you depict truth in your photography?

I don’t think there’s a definitive answer to that. It’s something that’s innate. It’s just in me. I never really know what I am looking for until I get there. I’m about interacting with a subject on a personal level, but I’m also experiencing the environment and all that is going on around me. It could be something they’re wearing, something on the street corner, the lightning, the front of a building, or rain. There is always a factor that influences my emotional response and that emotional response helps me put the pieces together in the moment. But even so, I never really know what I am doing until I push that shutter, and pushing that shutter is just as subjective as all the other pieces I’ve mentioned. That’s where the truth comes in, my truth. That’s where it’s not them, but what I put together. Richard Avedon is one of my influences for sure.

Could you give an example of a time when you purposely intervened in a scene to convey a specific message or emotion in the image?

I am consciously aware of every single thing that is going on around me. My peripheral vision is greater than 180 degrees. I am aware of every little moment and I never take my eyes off my subject’s eyes. I just feel it. I can certainly influence almost anything in order to get a reaction. It could be between me and the subject or a physical thing, like a dog walking into the frame. I’ll tell you about an image I shot of the group N.W.A. I took them to a beach because I thought it was incongruous with their image at the time and I thought it was kind of fun. I’m shooting these four guys who are sort of hard asses, you know? In my peripheral vision, I noticed a white surfer coming out of the water, walking behind them. I waited for the right moment and included him in the picture. It said so much and it made the picture so much more interesting. I’m open to anything to try and get the magic that starts to happen in front of my lens. If I can influence it, I will.

The depth and emotion displayed in your photos are truly lovely. Can you recount a difficult or emotionally charged situation you faced while taking a photograph?

There are times when things will emotionally touch my heart, but it’s all emotional to me. I’m an emotional person. My opportunities to connect with someone is a very emotional thing and it’s very important. I remember photographing a group of elderly people. Some of them were handicapped and others were in wheelchairs, but they all came together to sing. They sang rock songs. They sang a song from the Talking Heads, but it was basically a choir of octogenarians. It was so interesting. The director who did this was giving them purpose and a form of entertainment. It was so bizarre, but it was really great. There was something emotional about it and I was really happy that I was able to participate in it. Even the Yoko Ono image you mentioned, it was thefirst outing months after John [Lennon] was killed. It was really special to be with her and Sean [Lennon]. I am very close friends with Julian Lennon as well. All of the relationships I have built are emotional to me.

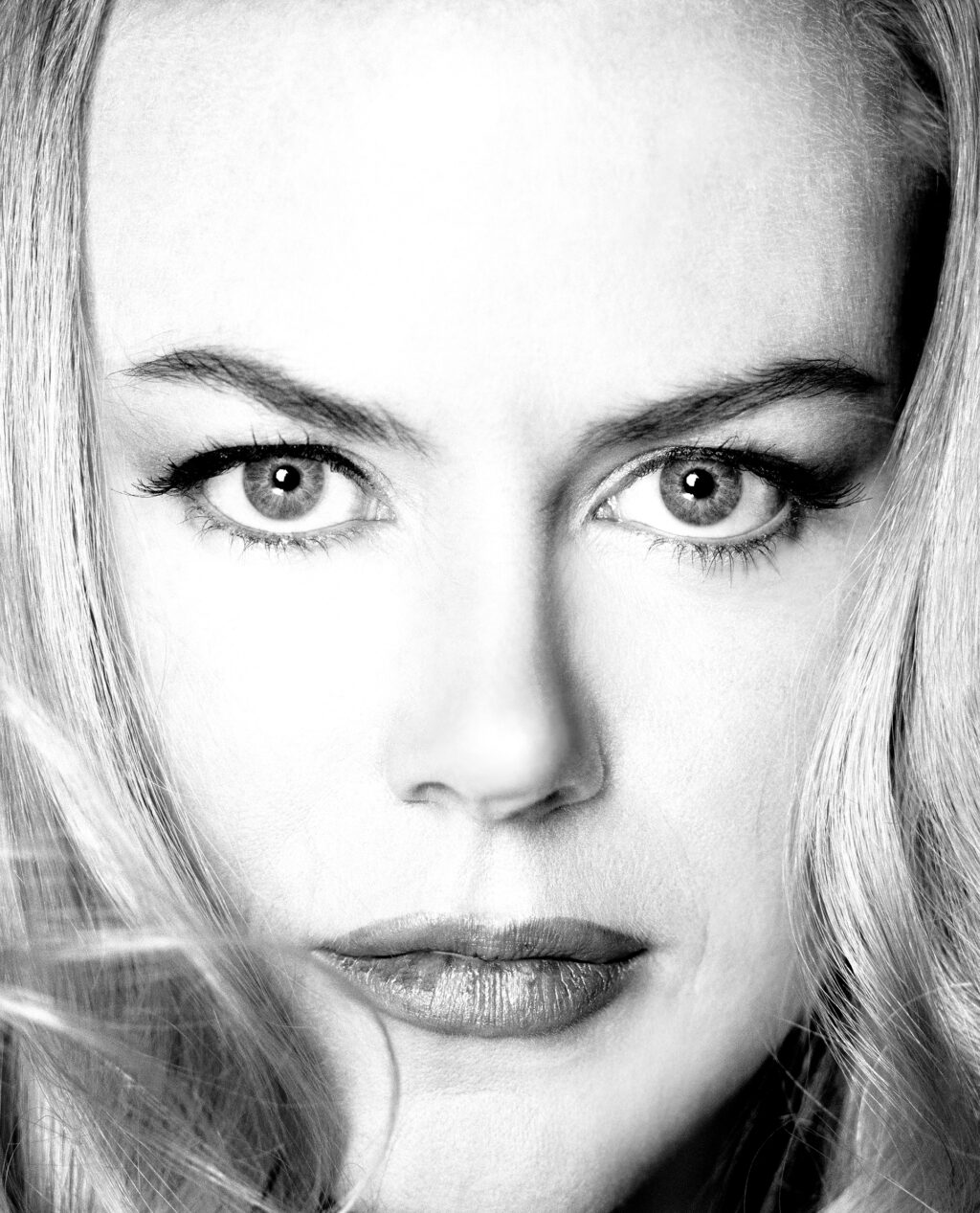

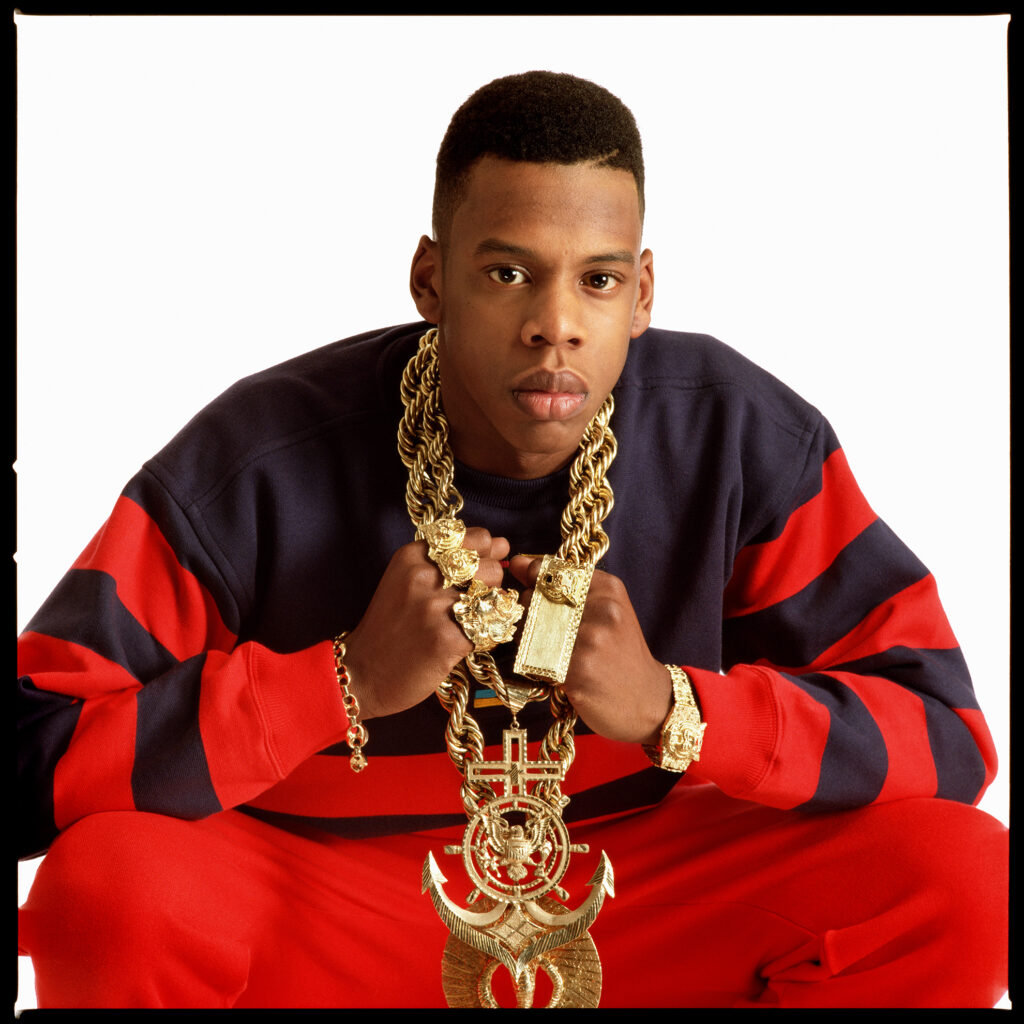

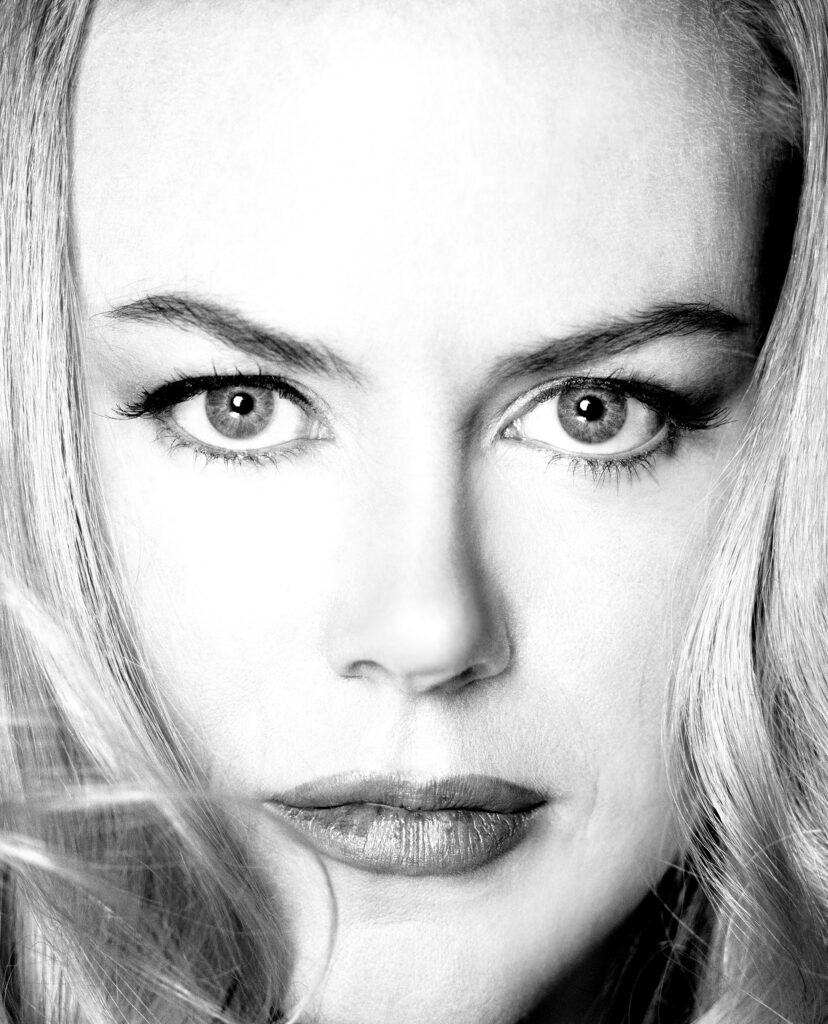

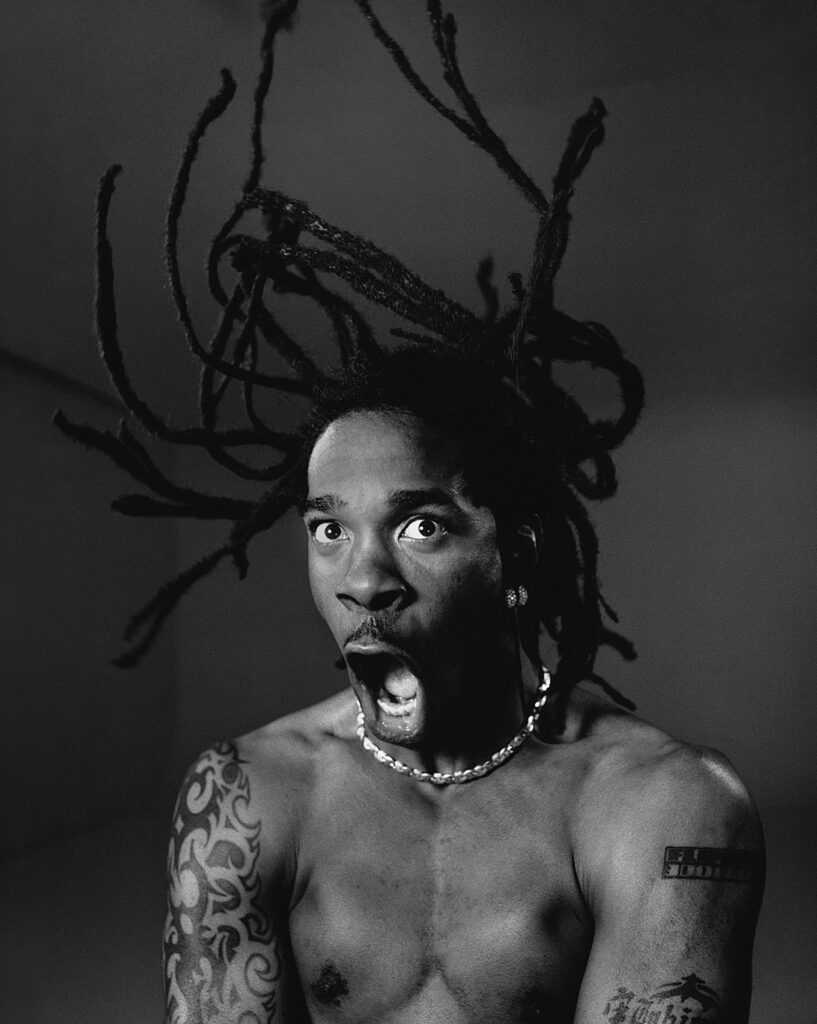

You have photographed a variety of subjects, from timeless beauties like Audrey Hepburn to influential rappers like Busta Rhymes. Is there a specific moment or shoot that particularly stands out to you?

My photos are like children. They’re all great. Each photo shoot is a very unique experience for me. I make it so. I don’t just go in and somebody stands there and has their picture taken. It’s an interaction between my subject and I that is sometimes lengthy and sometimes, brief. Nonetheless, I approach it the exact same way. I try to connect and make something happen. There is a photo I took of Robert Mitchum in 1988. It was a turning point in my career because I realized in that moment, through the picture I took, that I had transcended from taking pictures to making pictures. Even though it was just a headshot, it transcended something for me. It was kind of my recognition of a true use of the art form.

In your opinion, what are the key elements required for a portrait to truly resonate with viewers on an emotional level?

People often say they see me in my images. They see the people reacting to me and that makes me feel like I have taken a very successful photograph. I think there is a story in every photograph, but it doesn’t necessarily have to be about the person in it. The composition, the lighting, or the elements in the image can also emote something. That’s where the truth part comes in. It’s mine. Each photograph is something that I am making, not taking.

Do you believe your photography has challenged or changed the public’s perception of certain celebrities?

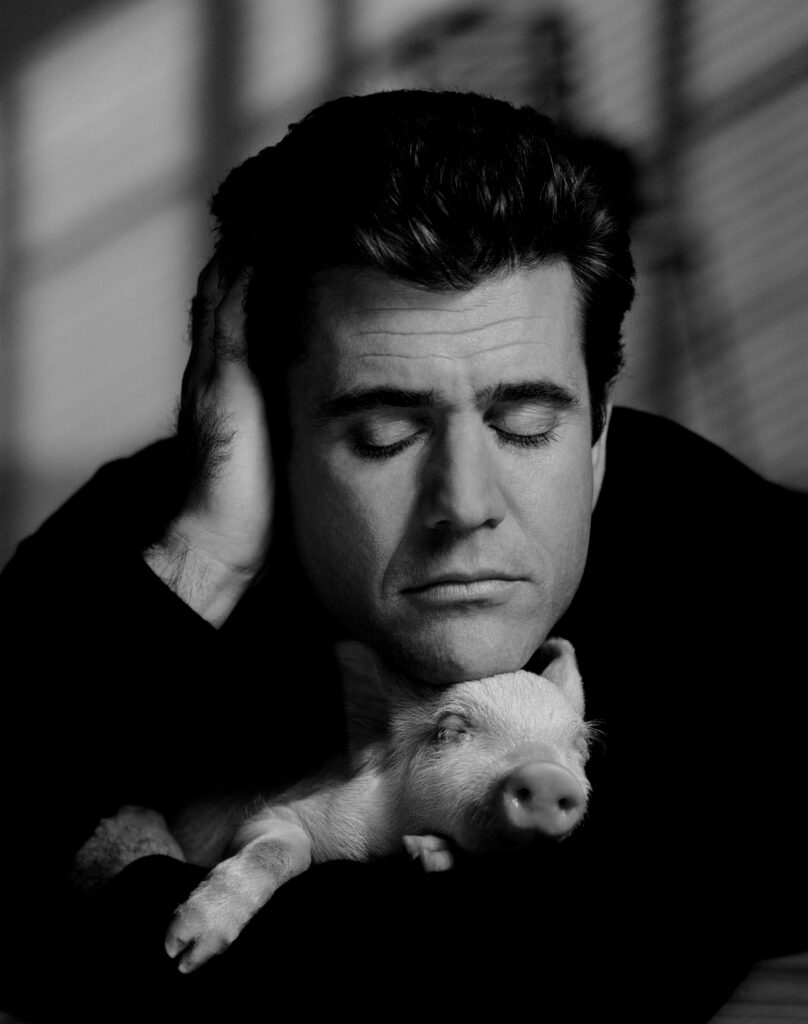

Not really with an intention, but I think so. A lot of my photographs have whimsy to them and I think sometimes that comes across and people can be surprised by certain elements or actions, like Elizabeth Taylor giving me the finger. I think there is beauty in glamour and in a lot of the work that I do, yet it is not overly stylized. There is a reality to the glamour that comes forth. I think that can be a surprise to people because when you look at a photograph of someone and it’s over touched or stylized, it’s beautiful, but it’s not really them. It’s certainly more common today, as everybody has a filter on their phone, but I try to make my imagery timeless and as real as possible.

How do you encourage your subjects to have a sense of spontaneity in your images? How do you make them feel comfortable and at ease to be themselves on set?

I’m talking to them all the time. I’m very engaged with my subjects. I try not to talk about the purpose of why we are there. I try not to talk about their new movie or their new book or what they’re promoting. I focus on other interests and it usually evolves from there. I am very comfortable and I know a little bit about a lot. I’m not afraid to talk and ask questions to learn about people. I always look at their eyes and that tells me if I am connecting with them, if I am losing them, or if I need to pivot. I just need to keep them focused on me while I perfect the composition I am creating. Somehow in all of that, I always find something.

I read that you would travel from Los Angeles to New York every two weeks to photograph your aging parents for a book. Can you elaborate on this?

My parents have now passed on, but during the last 10 years of their life, I started photographing them. It’s really an extensive body of work. In fact, it’s some of my best work. They are really great pictures, but they were just subjects, not models. I used them to make pictures, but inevitably, it was the last 10 years of their life. I even photographed them after they passed. I am curious about how you think your perspective on aging as a photographer differs from societal perceptions of aging. I am very conscious of time and in every way, photography is about time, isn’t it? It’s a document of something that either lives on or is only a single moment, but no matter what, it’s about a moment. It’s about the moment you push the shutter. As a portraitist, it’s also a moment of the subject that will never ever be the same again. There is always a moment in time we are preserving.

Could you share more about the memoir you are writing?

It’s funny you should ask, as I have a meeting with my publisher in about 30 minutes. It’s something I’ve been working on for a while. I’ve been jokingly telling my friends that you go to your therapist to talk about your childhood and you talk about now, but the book has made me think and look at all that has happened in between. It’s been a really great experience and I am really jazzed about it. I spend my time pointing my lens at other people and in this case, I’m pointing the lens at myself. I’m revealing things about myself through my life experience, and I don’t think I’ve ever done that. It’s not that I’ve hid behind the lens because like I’ve described, I’m just the opposite. I’m out there and connecting with all of my subjects, but nonetheless, this is definitely revealing what I’ve learned in life.

Does it make you nervous to reveal so much of yourself and be so vulnerable to the world?

I wouldn’t say nervous, but I’m aware of my vulnerability. I kind of feel like I need to or want to. I have also found that this has been a really interesting creative process for me because I’ve always been a storyteller, but a visual storyteller. Now, I’m getting that creative pleasure from writing.

@timothywhite

timothywhite.com

Timothy White is represented by Art Solutions LA.

All featured images are available as limited-edition prints at www.artsolutions.la